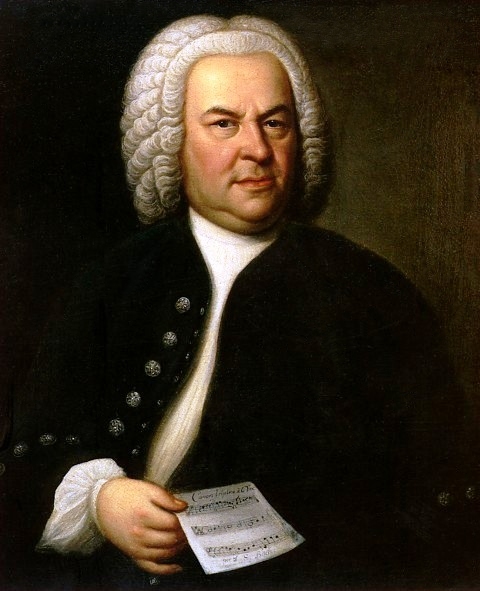

A masterpiece withstanding the test of time, Johann Sebastian Bach’s Mass in B minor, is an experience anyone should seek. I performed it this past weekend with the Apollo Chorus of Chicago under the direction of Stephen Alltop at Wentz Hall in Naperville, IL. It was the choruses’ premier at this concert hall, and what better way to introduce oneself than to perform Bach.

A masterpiece withstanding the test of time, Johann Sebastian Bach’s Mass in B minor, is an experience anyone should seek. I performed it this past weekend with the Apollo Chorus of Chicago under the direction of Stephen Alltop at Wentz Hall in Naperville, IL. It was the choruses’ premier at this concert hall, and what better way to introduce oneself than to perform Bach.

When I first found out that we would be performing this work, I was elated. Bach is a most treasured composer of mine, not only due to his profound pieces, but understanding his whole purpose of composition. I knew that this piece would be very difficult, but truly rewarding and I looked forward to the challenge. The first few rehearsals were troublesome for me, realizing the intensity of music. Containing fluid suspensions, rapid melismas, and a high tessitura, I knew I would have to learn more about my voice to perform this piece to the best of my abilities. To avoid vocal exhaustion, I had to continually be aware of the weight of my voice. Singing heavily would be counterintuitive and I already am aware of this issue within myself. This gave me the opportunity to work on control, to sing lightly with no vibrato while maintaining a full sound. Though I am still working on preventing myself from becoming too heavy on my voice, I have already learned so much and can translate it to the solo pieces I am working on.

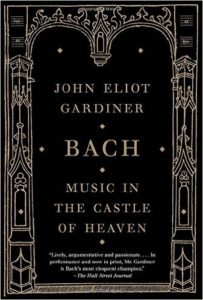

From start to finish, Bach gave this piece it’s own majesty. From the opening pleas of mercy at the Kyrie to the finishing Dona nobis pacem. Bach was a theologian, owning a large library of theological books himself, and used music to interpret the text. From the biography on Bach by John Eliot Gardiner (Music in the Castle of Heaven), he brings us Martin Luther’s perspective on music, who influenced Bach and his workings.

“In his Table Talk (of which Bach later had at least one copy) he said, ‘Music is a conspicuous gift of God and next [in importance] to theology. I would not want to give up my slight knowledge of music for a great consideration. And youth should be taught this art; for it makes fine, skilful [sic] people'” (40).

Throughout his Mass in B minor, Bach used a combination of text painting and different techniques in choral writing to portray the message of the gospel. From the program notes of the Apollo performance, director and conductor Stephen Alltop notes the “…elaborate vocal fugues, such as the ‘Kyrie,’ concerted choruses with brilliant orchestral accompaniments, such as the ‘Et resurrexit,’ strict stile antico based on the cantus firmi such as the ‘Confiteor’ and ‘Credo,’ and even double-chorus polyphony in the ‘Osanna.'” Later he writes on the text painting “…such as the stunning progression in the ‘Crucifixus’ down to the choir’s lowest range in the ‘et sepultus est.’ In the Credo movement ‘Et in unun deum,’ Bach gives a literal depiction of the text ‘ begotten, not made’ by having the one vocal line exactly imitate the other.” From my own observations, Bach indeed alludes to the movements among each other. The first setting of the “Et expecto” contains rich chords that encompass a similar sonority of the pleas from the initial “Kyrie.” This second experience of cries for mercy in the setting of knowing what mercy God has granted brings us to an awe and a complete stupor of the gift of eternal life. This realization of eternal life in the second setting of the “Et expecto” contains complete joy and bliss that reminds the listener of the “Et resurrexit,” both of which are in the key of D major; the relative key of b minor.

This work itself is an enigma and raises many unanswerable questions, but brings much wonderful speculation. Why would Bach compose a mass, which would never be performed in a Lutheran church setting and most likely never be performed in a Roman Catholic service due to the length? One of my favorite observations is that he created this piece as a culmination of all that he has done. It is a work encapsulating a majority of his life, containing music he had already written such as the first chorus of his Cantata 29, Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir, and Cantata 215, Preise dein Glücke, gesegnetes Sachsen. Completed in 1749, the year before his death, it is as if he created this piece as an autobiography of his music, using a text setting that many other composers had already set to music. He wanted to create this masterpiece as a remembrance of his name, to never be forgotten, and live on forever.

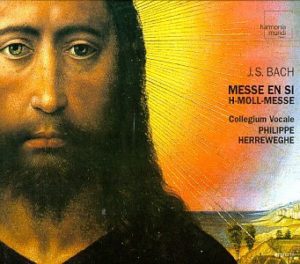

Below you will find some supplemental material to peruse your interest in the life and works of Johann Sebastian Bach. Truly an inspiration to many and whose ministry has extended past his own lifetime.

-

-

“Music in the Castle of Heaven” by John Eliot Gardiner

-

-

“Mass in B minor” conducted by Philippe Herreweghe

-

-

“The Essential Bach Choir” by Andrew Parrott

cantus firmus – a reappearing melody line forming a polyphonic composition

melismas – succession of multiple notes on one syllable of a word

polyphony – two or more lines having separate melodies at the same time

stile antico – “ancient style” was a prominent form of polyphonic composition in 16th-century church music and continued to through the 17th century.

tessitura – the range of the vocal line where the majority of the notes lie